Since 1971, British author Peter Ackroyd has written well over fifty volumes of fiction, non-fiction and poetry. My first encounter with him was Hawksmoor, a 1985 novel based loosely on the life of 18th century English architect Nicholas Hawksmoor.

Hawksmoor himself had already drawn the attention of scholars and others interested in post-1950 historiography. I recall Bill Burgett’s scant treatment of Hawksmoor during an architectural history class in 1966—thanks, Bill—a time when Hawksmoor was generally consigned as the assistant or “clerk-of-the-works” for Sir Christopher Wren and then as the sidekick of Sir John Vanbrugh; his few credited works were wedged uncomfortably somewhere between Wren’s prodigious output of post-fire churches and Vanbrugh’s “Blenheim”, an enormous country house built for the 1st Duke of Marlborough—“a gift from a grateful nation” for his victory in the eponymous battle during the War of the Spanish Succession. [Which war, not incidentally, received equally scant coverage in my high school world history class, taught by the basketball coach and, if memory serves, consisted of making hand-colored maps, by the dozen. History was not my best subject—nor was it his. I grew to love geography instead.]

The arc of Hawksmoor’s historiography brought him, in multiple senses, out from the shadows of those two better-known architects of the English Baroque. About the time I began my teaching career, Hawksmoor’s works—there weren’t that many of them identified then, which partially accounts for the slight attention paid to him ca1970—were beginning to appear in The Architectural Review, a London architectural journal. But since that time, his contributions to both of his “mentors” has required a true biography be written. In the meantime, he was,

“…the subject of a poem by Iain Sinclair called ‘Nicholas Hawksmoor: His Churches’ which appeared in Sinclair’s collection of poems Lud Heat (1975). Sinclair promoted the poetic interpretation of the architect’s singular style of architectural composition that Hawksmoor’s churches formed a pattern consistent with the forms of Theistic Satanism though there is no documentary or historic evidence for this.” [It took more than a year to track down my copy of Lud Heat from a British O.P. bookshop and is probably worth a lot more today. Now, where did I put it?]

Not one to ignore such a tantalizing prospect—few enough architects are linked with Satan—Peter Ackroyd accepted this as context for the ‘85 novel; I immediately bought and read it almost without pause. Forty years don’t seem to have passed. [I should confess having already seen three of Hawksmoor’s surviving churches during trips to London in 1971 and 1977 and that that experience only encouraged me to look more closely into his career.]

The post-modern structure of Hawksmoor [though you couldn’t prove it by me] plays with time, shifting forward and back between 18th century architect Nicholas Dyer (patterned on the actual Hawksmoor) and a fictional 20th century Scotland Yard detective Nicholas Hawksmoor. They share a Manichaean view of the world as profoundly evil and might easily have been a prototype for Sweeney Todd! “Raise your hatchet high, Nicky. Raise it to the sky.”

Dyer commits a hidden human sacrifice at each of the six actual Hawksmoor church, concealing the body in each foundation. Then, in alternate chapters, DCS Hawksmoor investigates parallel modern crimes at each of those sites. For anyone who’s been to London more than once, Ackroyd’s psycho-geographic description of the place is palpable; it was as though I walked with him? In the final chapter a plot twist involves a seventh church, invented by the author, as well as a similar unsolved crime and the detective’s virtual evaporation, just as Dyer had done a chapter earlier. That seventh church hooked me: it was dedicated to Little St. Hugh, a Christian “martyr” during the anti-semitic 13th century.

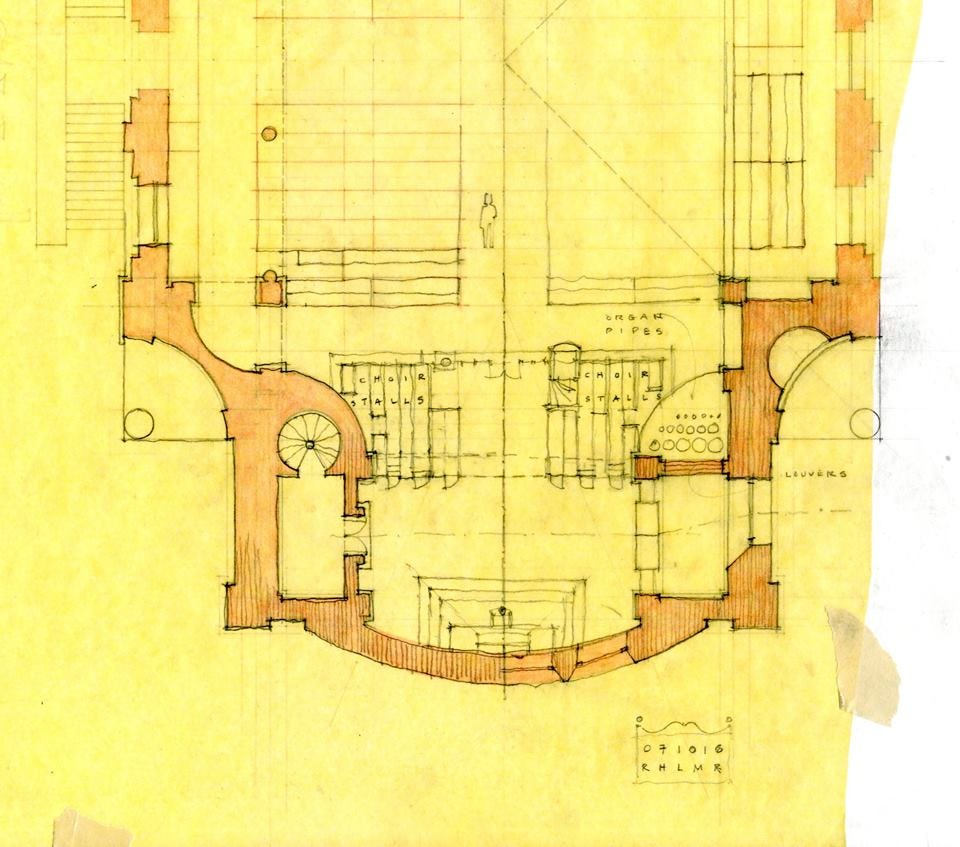

During his final trek through the City of London, intent to perform the required ritual sacrifice, the description of Dyer’s path is vivid and actual, up to a point, where it, too, enters the realm of fantasy. I remember completing the book late in the night of “day two” and waking with a vivid mental image of that church. I had seen it in a dream and knew it had to be committed to paper, before it disappeared like tears in rain. So, I hurried to school—we were in the Quonset then—strapped a sheet of vellum on the draughting board—we actually “draughted” then, like, you know, with a pencil—and drew for the next four or five hours as a plan and front elevation of the purported Little St. Hugh. It was the most intimate architectural dream state of my eighty years and hasn’t abandoned me during the most recent forty of them.

Could my Little St. Hugh be mistaken for a seventh Hawksmoor church design? I hardly think so. But my subconscious processed what I knew then of his work and has continued to evolve with more recent scholarship, joining the list of “stuff to be completed” prior to my lying down for the oft-mentioned dirt nap.

Yes, I spend a goodly amount of time “living in the past”. But the operative word is living, the present being not an especially tolerable place.

For information on Hawksmoor, the architect, visit here.

For Hawksmoor, the novel, look here.

And to learn about Little St. Hugh of Lincoln, try this.

To learn more about Iain Sinclair, you’re on your own.

Psychogeography, on the other hand, is worth exploration on its own.

As a footnote, I need to thank a former student (John) who spoke at my retirement gathering. John reminded me that I had guided him during our summer foreign study tour in 1977 (I think) while we were in London into St. Mary Woolnoth, which I have to admit is my favorite Hawksmoor church. I’d been unaware that our brief tour has had a long-term affect on him. It’s good to know that teachers can have positive influence—even though it may not be obvious at the time.